By Jessica Egerer, Bird Department Zookeeper

Just off the shore of Douglas Lake in Pellston, Michigan, sits a small, brown building, nestled in amongst the rest of the University of Michigan Biostation. It is inside this small building where big things happen! Here, countless avian professionals have spent periods of time working together to successfully rear piping plovers since the beginning of the recovery initiative in 2003. This year, I was lucky enough to spend a few days at the station in May and return in June!

During my stay in May, I helped prepare the building for the season. There was a lot of cleaning and organizing to do, as well as taking inventory of medical supplies and equipment. I also set up incubators, brooders and chick rearing boxes. To ensure successful development of the plovers inside the egg, the incubators must be kept at 37.5 Celsius and monitored closely. We operate some incubators dry to maintain low or no humidity, and others have their water chambers filled with deionized water to increase humidity. The eggs, as developing, require specific parameters and will sometimes be moved between incubators based on their weight loss and what type of environment is needed.

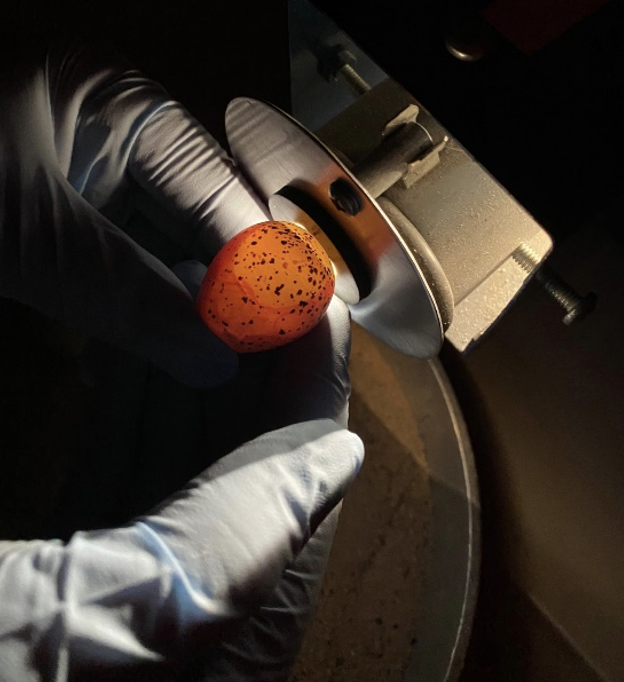

As eggs were brought in, we would place them in incubators and monitor them daily. Egg science is fascinating, and we can track the development of the embryos by candling them and weighing the eggs. Candling is when we shine a very bright light into the egg, through the shell, and look at what is going on inside. As the embryo develops, we will start to see veins and movement, and it can be a very exciting process! Weighing the eggs daily allows us to keep track of the weight loss of the egg. Eggs are porous and will lose weight in the form of moisture loss through the shell as the embryo inside is growing.

When I returned to the station in June, things started to pick up. I was working at the station during this time with Nicole Green from the Detroit Zoological Society and Bliss Capener from the Tracy Aviary. We had started taking in clutches of eggs that had been collected by field monitors for various reasons, including nests being washed out by flooding and nests being abandoned by parents due to nearby predators or the predation of one parent. We worked alongside the field crew to get the eggs transferred safely to the station.

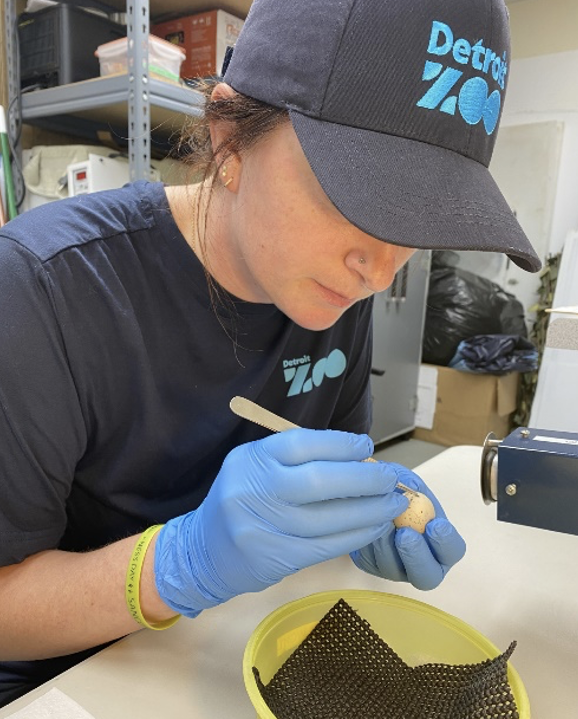

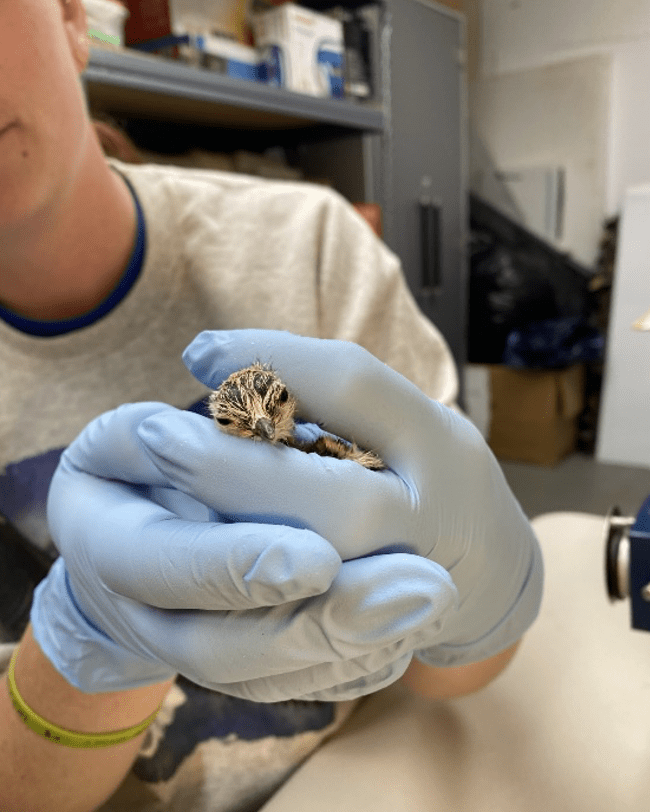

After approximately 23-25 days, we can expect the chicks to start hatching! Hatching takes a lot of energy, so the chicks will typically rest for a short while after they’ve first made their appearance. Because they are a precocial species, they are up and running around quickly thereafter. Occasionally, due to mispositioning inside the egg, we will need to assist hatch an egg. Due to the very small, fragile state of piping plover eggs we must be very careful not to damage the egg and instead use tweezers to help create a line of broken shell up into and around the air cell of the egg.

We continue to monitor the chicks closely as they develop and weigh them daily. We feed them black worms, meal worms, wax worms, crickets and mayflies. Other than picking them up to weigh them, we are very hands off with the chicks. We place them into chick rearing boxes, which replicate their natural beach habitat, and we play a recording of beach sounds. Eventually the chicks will graduate to using a pen that is connected to the building, that allows them indoor and outdoor access. Lastly, the chicks will move to the lakeside pen, experiencing a soft release as they zip along the shoreline, weave through some taller and more natural grasses, and practice flying. After about 30 days, the chicks will be banded for monitoring and released on nearby shorelines in upper Michigan.

I am incredibly honored to be a part of the piping plover captive rearing program. It is extremely rewarding to work alongside so many dedicated aviculturists and contribute to the success of growing the population of this extraordinary flagship species. Since its start, this initiative has increased Great Lakes piping plover pairs from 17 to 81, and I am inspired to continue helping them grow! Thank you for reading about my experience and some of the details behind the important work accomplished through this program. Forever rooting for these special shorebirds. Peep, peep!