It’s just before dawn in the Apalachicola National Forest of Northern Florida, and light is glinting off the dew of the long-leaf pine trees as the humidity peaks. These conditions are just right for one of nature’s most adaptable animals to undertake an incredible journey. A striped newt (Notophalmus perstriatus) stirs under the water of a temporary pond.

Today, this young newt is preparing to travel from the relative safety of this ephemeral pond, to which he has been introduced with the help of the Coastal Plains Institute (CPI) and the Detroit Zoological Society (DZS). CPI has been dedicated to preserving the long-leaf pine ecosystem since 1984 and continues to work to maintain this unique habitat through scientific research, land management, and environmental education within Florida. The striped newt, recently listed as “threatened” in Florida, needs all the help it can get.

This very pond where the newt plans to emerge has been constructed and maintained through the work of CPI. The DZS and CPI have been collaborating on releases such as this one since 2017, and this particular newt has been bred and raised at the Detroit Zoo by staff who specialize in amphibian care with this moment in mind, the opportunity to re-introduce species and preserve biodiversity.

The striped newt can adapt to life outside the water, an ability that amphibians have been perfecting for millions of years. When conditions are right, the striped newt’s skin will begin to thicken and granularize, helping to hold moisture more efficiently than its typically slippery and smooth skin. The newt’s tail will become narrow, round, and less like a paddle, making traveling over dry ground much more efficient. This life stage is known as an “eft.”

As the newt slips out from under the water and moves onto land, its bright skin coloration advertises its toxicity to any potential predators who wouldn’t mind getting an early morning snack. Moving deliberately through the ground cover, the newt encounters a drift fence and travels along the edge of it. After a few feet, it drops into a 5-gallon bucket, which CPI staff soon recovers and processes. This fence and the corresponding bucket are all part of a scientific study undertaken by CPI to measure the success of introductions such as this one. Monitoring these drift fence arrays is no easy task, and CPI volunteers are tasked with checking these traps every day for up to seven months of the year.

Many months ago, the amphibian care staff at the DZS’s National Amphibian Conservation Center (NACC) began preparing to breed our resident population of striped newts. All the conditions for reproduction had to be just right. The correct water quality, depth, and egg-laying materials were painstakingly researched and implemented. With the addition of a specialized water filtration system, known as a reverse osmosis system, the amphibian department staff had complete control over the “makeup” of the newt’s water. It could reach the correct parameters to mimic the natural environment where these newts live in the ephemeral wetlands of Florida and Georgia. The plumbing required for this filtration unit was installed and tested by the DZS’s maintenance staff. The work required careful drilling through the walls of the NACC to run plastic plumbing lines to deliver the filtered water to the bio-secure and husbandry spaces where animals are kept. This was no small feat and proved to be a great example of how the DZS’s conservation success is a team effort spanning all the departments of the Zoo.

After all this effort to prepare, the real success occurs when the striped newt begins the reproduction process. The male will hold the female in an embrace known as amplexus; during this embrace, the male rubs the female’s snout with his chin and releases pheromones, which are fanned towards the female with his paddled tail. Once the female is receptive, the male will drop what is known as a spermatophore. From this point, the female will accept the spermatophore, and internal fertilization will occur.

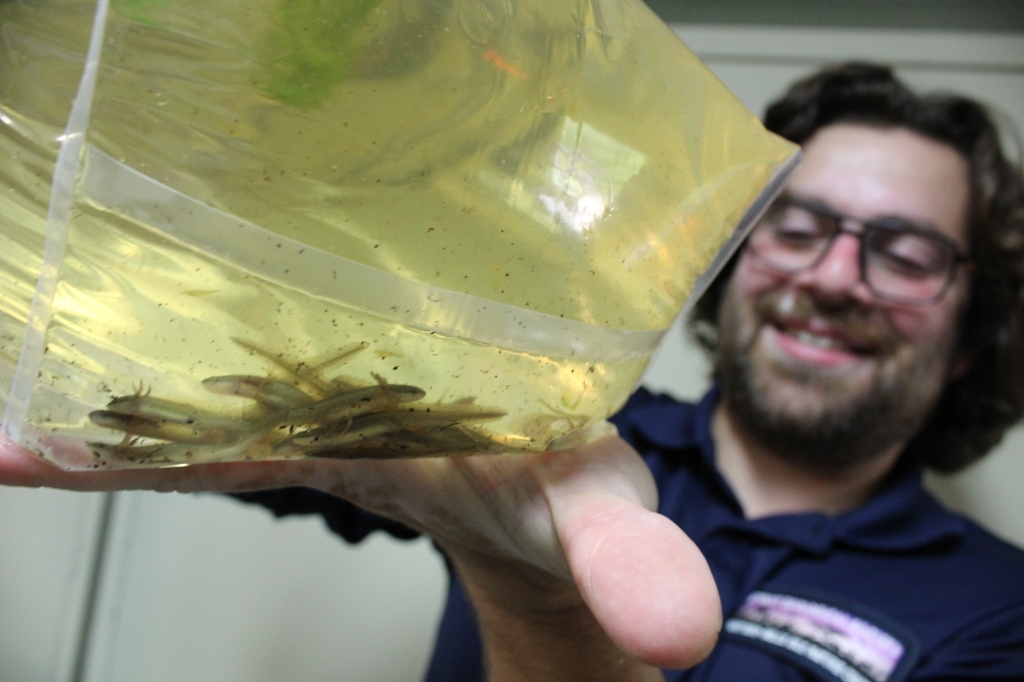

Once the eggs are laid, usually on long emergent vegetation that has been placed in the habitats of the striped newts, the baby newts will begin to develop. This process can take several weeks and can be affected by temperature. The larvae are tiny, sometimes measuring about 8 millimeters, and very thin, resembling a small piece of wood or a twig, making them difficult to see with the naked eye. These tiny larvae are fed small invertebrates and aquatic worms, which have also been cultivated by the talented staff at the NACC. Once the newts have reached about 13 millimeters, they are eligible for release, counted and carefully shipped to Florida when conditions are just right in the wetlands for release.

After a long journey from an egg in the bio-secure breeding room at the NACC to the Florida wetlands, our newt is now being counted and sent into the forest by the staff and volunteers at CPI. This newt will likely spend years in this “eft” life stage, moving through the long-leaf pines and feeding on invertebrates. If conditions are right in the coming years, the newt will be beckoned back to the temporary ponds by rainfall and favorable environmental conditions, where it could potentially breed naturally and help bolster the numbers of this unique and increasingly rare amphibian. In 2023, the DZS and CPI introduced 227 striped newts back into the wilds of Florida, increasing the numbers of this important animal and furthering the case for collaboration in conservation.

The striped newt repatriation project ended the season with a beautiful surprise. Several months ago, CPI staff dip-netted two large, gilled paedomorphs out of the new, rubber liner-enhanced release pond, where CPI staff released 227 young larval striped newts. The newts had been raised here at Detroit Zoo, sent to Florida on July 11, then released on July 12 after an acclimation process. In the coming weeks, four of the 227 were encountered in drift fence buckets and inferred to be exiting the pond and going terrestrial as efts. No others were seen after that. We worried that most animals were lost to predation by turtles and predaceous invertebrates. However, to end the season and ascertain whether some newts had survived and opted to live an aquatic life, CPI captured the two paedomorphs.

These paedomorphic animals may represent a persistent aquatic ‘population’ there. We hope and expect they will go on to reproduce. That will be determined next year by dipnet and drift fence sampling. This is the best news of the 2023 striped newt repatriation project field season and one of the highest points in the 11-year ongoing recovery efforts.

Dr. Ruth Marcec-Greaves downloads six months’ data from the weather station.

Dr. Ruth Marcec-Greaves downloads six months’ data from the weather station. An Amphibian Protector’s Club member observes a frog up close on a night hike.

An Amphibian Protector’s Club member observes a frog up close on a night hike.