In 1984, the Puerto Rican Crested Toad became the first amphibian to be included in the Species Survival Program. In 2021, this initiative evolved into the Puerto Rican Crested Toad Conservancy — a nonprofit organization uniting zoos, individuals, and institutions to protect the crested toad and its habitat.

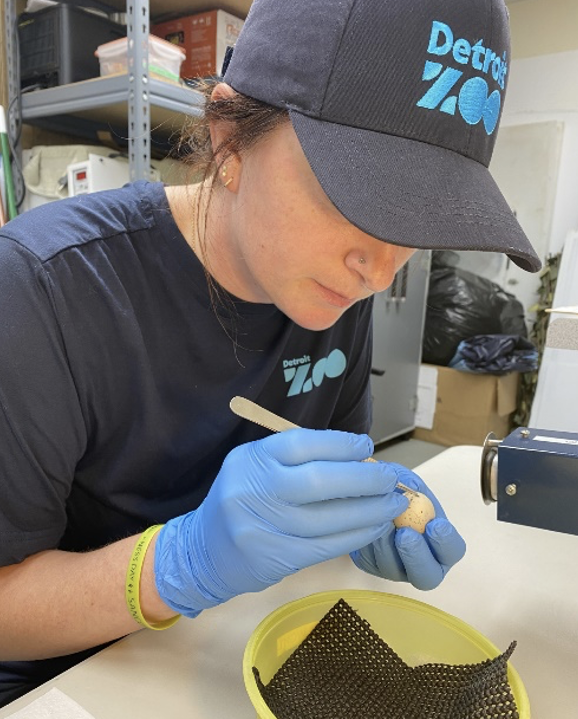

As an active member of this consortium, the Detroit Zoological Society has proudly contributed more than 129,000 tadpoles to release efforts in Puerto Rico. Zookeeper Maya, a dedicated caretaker and breeder of this species for nearly two decades, has played a vital role. Her extensive experience and precise care have allowed her to successfully breed and raise thousands of critically endangered tadpoles from egg to release-ready stages, ensuring their contribution to conservation efforts.

In December 2024, Maya had the opportunity to travel to Puerto Rico to participate in habitat restoration and reintroduction surveys. She reflects on her transformative experience in the following prose.

PUERTO RICAN CRESTED TOAD

About the Puerto Rican crested toad,

They live mostly in crevices, not so much in holes.

They start off in shades of soft pink and then the boys fade into a green and gold.

As they get older, their colors are more dirt brown and a lot less bold.

But they still maintain their beak-like turned up nose.

Puerto Rico’s national frog is actually a toad.

We send thousands of tadpoles back without fear, but they are still critically endangered, my dear

The Detroit Zoo’s efforts are bringing their numbers up more each year. We won’t stop until they can get their own breeding into gear.

I am truly grateful I could make the trip this year.

THE TRIP

I was off to Tamarindo to help make the PRC toad story longer,

By scouting new breeding sites and making their breeding ponds stronger.

Pulling weeds and using rocks to hold up the ponds edge, breeding ponds T1 and T2 were far from dead, we would make sure these ponds would hold more water longer than it ever had.

We evicted the invasive Marine tadpoles. It was way pass time for them to find another watering hole.

These ponds were being rebuilt for the PUERTO RICAN CRESTED TOAD!

We had built it with hopes that the toads would come, for their natural pond had succumb to Salt and Sun.

When we had finished a prayer went up for the rain to come, but all we got were chiggers, hot weather, dirt and even more sun. The DNR assured us that the rain would come.

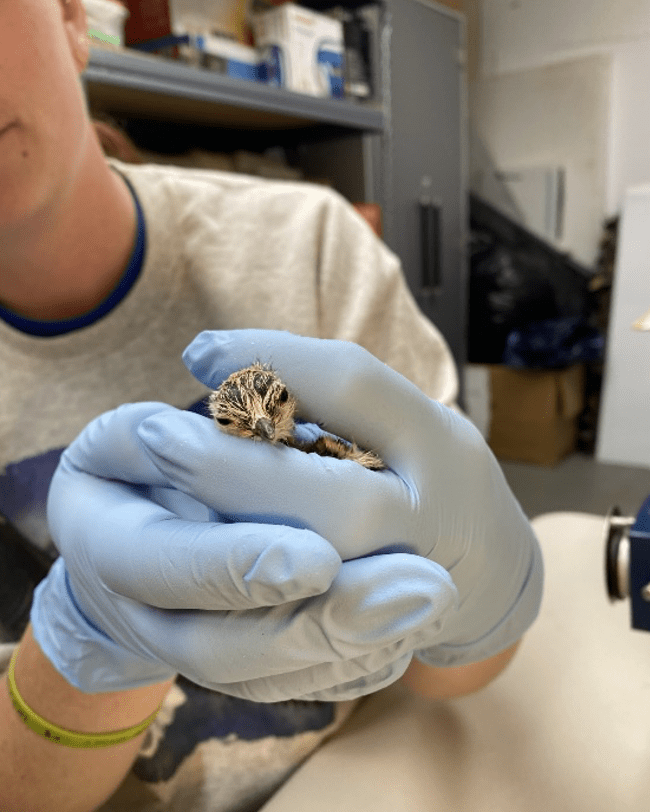

We left the next day for El Tallonal to release baby PRC toads that had been head started back at home, these would be released in a rainier home.

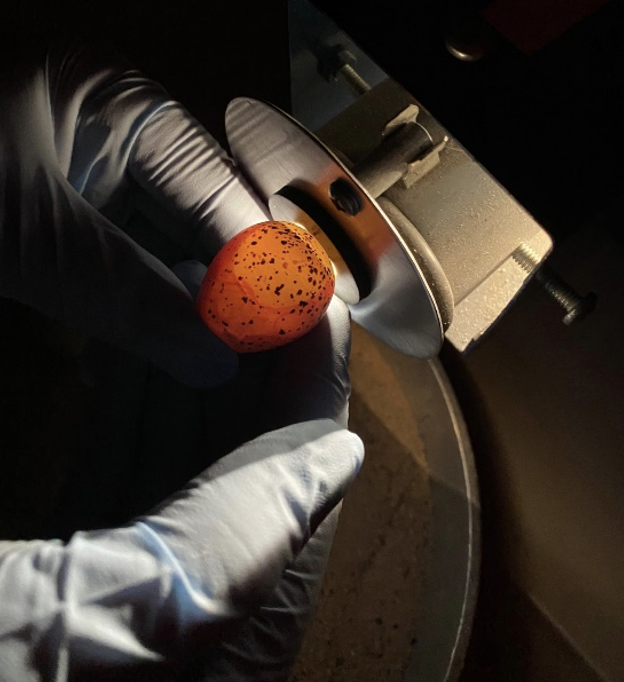

The bigger ones were tagged and had a tracking collar. The smaller ones were dusted with bright-pink, fluorescent Cheeto-like powder.

Toads were dusted and tagged thru out the night. They had to be ready for release long before first light.

Some were released in holes on long and steep Mountain trail, while the rest were let go in and around a caged pond owned by Casa de Abel.

No rest for the wicked, up before light. It was so early, I thought it was still night. Armed with radio trackers and black lights, back up the trail to see how far the toads traveled throughout the night.

Some were content with where they had been placed. Most moved far and wide with great haste. Some went further still, just too far for us to give chase.

Oh well, time to load the vans and head to the next place.

To a suburb about an hour, give or take, outside of Old San Jaun, we had a place somewhere in Bayamoʻn.

The Virgin Island Boa was what we came to catch and survey, our permits were signed, so we headed out without delays.

Head lamps on every tree, bush, and plant, we searched for about a two-mile stretch. Luck was truly on our side I must admit, 3 BEAUTIFUL snakes we did get.

Once examined, weighed, measured and bagged, back to the room for a shower and bed, I couldn’t have been more GLAD.

The next night Lady Luck had abandoned us, not one Boa seen, not even the scent of their musk. We’ll get them next time, on that you can trust.

My adventure had sadly come to the end. I had a great time being dirty, smelly, and bug-bitten with new friends on whom I could depend. Heading home scratching and hoping my bug bites would soon dry up and mend.