Do you know what it’s like to be a giant anteater? How about what the world looks and sounds like if you are an 18-foot tall giraffe? High school students taking part in the Detroit Zoological Society’s (DZS’s) animal welfare summer camps had the unique opportunity to experience just that.

Over two weeks, 31 students participated in activities based on the Center for Zoo and Aquarium Animal Welfare and Ethics’ “From Good Care to Great Welfare” workshop, which annually draws professional animal care staff from around the world. The goal of these immersive exercises is for the students to better understand the world from the perspective of another species.

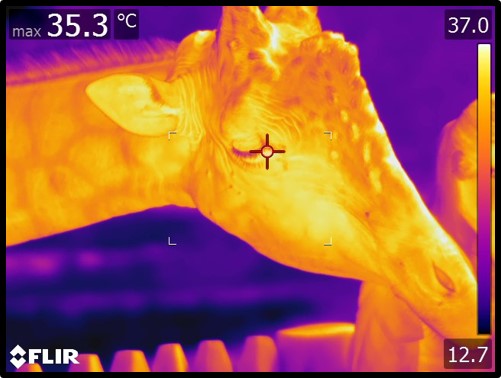

What we pay attention to in our everyday lives is based on what is meaningful to us. When we make an effort to put ourselves in the place of another being (or as close to it as we can), we become aware of the factors that may impact them, even things we had never noticed before. The students noted that when they were “anteaters”, they focused more on what they could hear and smell. When they were elevated to the height of Jabari, the male giraffe who lives at the Detroit Zoo, they could see the neighboring golf course. They wondered if that is an interesting thing for the giraffes to see. Not all humans like golf, but what do giraffes think of the view? Different species – and different individuals within a species – have different preferences, and we have to pay attention to that to ensure they experience great welfare.

In addition to the immersive exercises, the students also studied the behavior of the two giant anteaters at the Zoo to better understand how they use their habitat and which environmental features they seemed to prefer. They used all of the knowledge they gained to design a new habitat for the anteaters as their final project. It was really impressive to see everything they incorporated into their models, and the reasons they gave for the choices they made. The students participated in a lot of other activities, including working with a staff member from the Humane Society of Huron Valley on positive reinforcement training with one of the amazing adoptable dogs from the shelter. DZS staff made videos documenting the camps, and it was so great to hear how the students are going to take this information with them and apply it to their own lives, including with the animals that share their homes. We had a great time working with everyone and sharing knowledge to inspire the next generation to be aware of and champions for animal welfare.

– Dr. Stephanie Allard is the director of animal welfare for the Detroit Zoological Society and the director of the Center for Zoo and Aquarium Animal Welfare and Ethics.