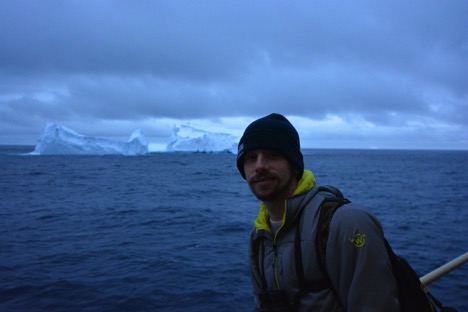

Happy New Year from 64°46’27” S, 64°03’15” W!

In Antarctica this time of year, the nights are very short – the sun sets around midnight and rises at 2 a.m., so it never really gets dark. As the days pass, many icebergs drift by and their variation and beauty leave me in awe. From small to huge, they come in any shape you could imagine and they express a variety of whites and blues.

It is snowing a bit less, and the islands are starting to melt down a bit, which exposes the rocky cliffs and reveal a variety of different lifeforms. Antarctic hair grass is one of only two species of flowering plant found in Antarctica, and mosses and lichens paint the rocks on the islands in greens, yellows, oranges and more. Lichens are organisms made up of a symbiotic (or mutually beneficial) relationship of a fungus paired with algae and/or cyanobacteria.

This nice break in the weather allowed us to make our way further south to conduct a survey of gentoo penguins. This species of penguin is the third largest in the world and there are currently around 300,000 breeding pairs worldwide. Where we are right now is on the southern extent of their range. It’s exciting to see this particular species in the wild, as gentoos are one of the four species of penguins at the Detroit Zoo. And while I’ve been in Antarctica, 20 additional gentoo penguins arrived at the Zoo as we prepare for the opening of the Polk Penguin Conservation Center in April.

Our team split up into groups and together we achieved a full survey of gentoo nests on the island. Most of the birds are incubating two eggs each in nests formed out of rocks. The sun peeked out of the clouds and lit up the sky as we marched from colony to colony.

We also had some excitement as we were counting Adelie penguin colonies when we heard some faint peeping noises. The next generation of these amazing black and white birds had just started to hatch. A couple of lucky parents had very young chicks so small the gray downy bird could fit on your hand. We could see that many more birds were about to hatch as well – multiple eggs had externally pipped, which means that the chick has cracked or put a hole through the eggshell. Very soon the colonies will become incredibly noisy and messy! In the coming weeks, we will see the parent’s inexhaustible efforts as they travel back and forth from the ocean to the nest to feed and raise their young.

As is the case with many bird species, the chicks of Antarctica have to grow extremely quickly. Because the summer season (providing warmth and abundant food) is short, the young birds must grow quickly and prepare for migration or become ready to brave the harsh winter.

Brown skuas are also starting to hatch and soon the giant petrels will as well. We have been doing a lot of monitoring of the giant petrels and have identified almost all of the breeding pairs in our study area that have eggs. The giant petrels take turns incubating, with one bird at the nest, while the other bird goes foraging. Once we get the first parent’s band number, we wait about a week to let the birds switch roles. Then we can get the other parent’s band number while it is incubating the egg. All of these hatching chicks should keep us very busy in the upcoming weeks.

Throughout our travels, we have been keeping our eyes open and are listening for blow spouts as humpback whales are usually in the area this time of year. Over the past weeks, we have had a few sightings of minke whales and we had a pod of orcas come by right in front of Palmer Station. The orcas were popping their heads up out of the water looking for seals on the ice floes. This behavior is known as “spyhopping”. It was incredible watching these iconic, powerful animals work the inlet by station.

Thanks for reading; I will report back soon!

– Matthew Porter is a bird department zookeeper for the Detroit Zoological Society and is spending the next few months at the U.S. Palmer Station in Antarctica for a rare and extraordinary scientific opportunity to assist a field team with penguin research.

We are just passing the tip of South America, headed for the Drake Passage. Wish us luck and calm seas! The next time I report back, we should be on land at the Palmer Station.

We are just passing the tip of South America, headed for the Drake Passage. Wish us luck and calm seas! The next time I report back, we should be on land at the Palmer Station.